Today, we continue the series on Scandinavian design we have began with the previous article “Scandinavia’s Post-War Design Legacy”.

We’ll uncover what defines this design movement—from its foundational principles to its global rise—and examine how its quiet elegance continues to shape the way we think about home today.

We’ll look at the visionary architects and designers who pioneered the movement—Kaare Klint, Alvar Aalto, Arne Jacobsen, and many more—and the philosophies that guided their work: simplicity, utility, craftsmanship, and social responsibility.

We’ll also investigate how, after World War II, Scandinavian design became a symbol of progressive modern living, especially in the United States and Australia, where its influence spread rapidly through exhibitions, mass production, and an appetite for honest, beautiful domestic spaces. Enjoy!

(Marco Guagliardo - Mid-Century Home’s Editor in Chief)

In the decades leading up to World War II, Scandinavian architecture and design were already converging towards a synthesis of vernacular tradition and the emerging ideals of Functionalism. In Denmark, Kaare Klint (1888–1954) drew on local woodworking vernacular and the Arts and Crafts movement to teach a generation of designers at the Royal Danish Academy that beauty arises from three principles: proportion, craftsmanship, and utility.

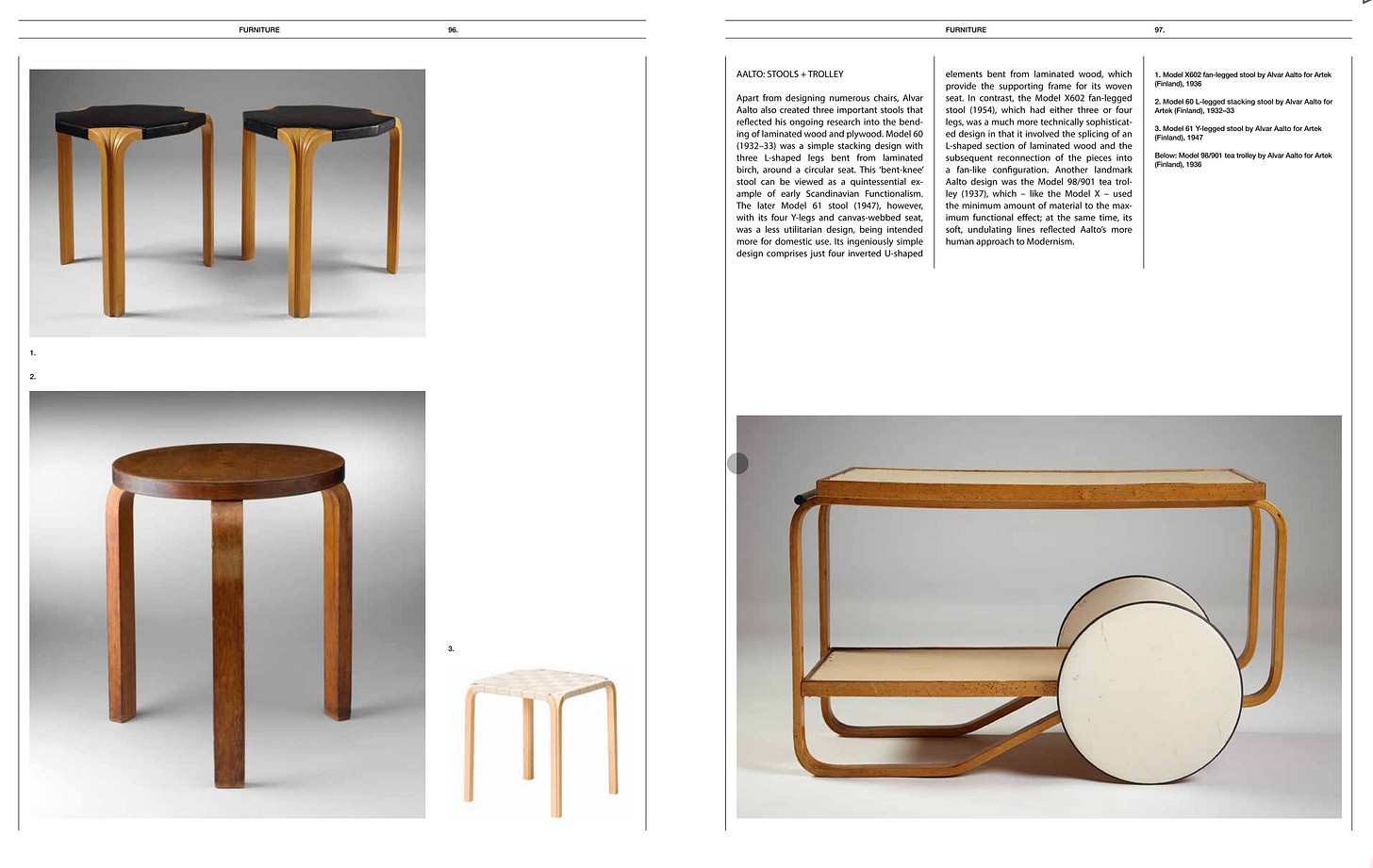

His Faaborg Chair of 1914 distilled the curved lines of 18th-century seating into a spare yet welcoming form. Meanwhile, in Finland, Alvar Aalto (1898–1976) balanced Nordic Classicism with Modernism, experimenting with laminated bent-wood in furniture and pursuing organic geometries in buildings like the Viipuri Library (1927–35). Across the region, Poul Henningsen’s layered PH lamps (1925) married rigorous research on glare with poetic clusters of opaline shades, making light itself a sculptural and social medium.

The war years and their immediate aftermath marked both a rupture and an intensification of these tendencies. While Scandinavian countries were spared extensive bombing, they felt acutely the imperative of reconstruction and social welfare.

The Swedish government’s Million Homes Programme and Norway’s housing cooperatives commissioned architects to rapidly deliver well-appointed but economical housing. Material shortages drove innovators to standardize modular components and champion local softwoods—birch and pine—for everything from structural panels to cabinetry. In 1943, Sweden’s design council, Svensk Form, reoriented itself toward “design for democracy,” showcasing furniture that could be mass-produced without losing its tactile warmth.

After 1945, “less but better” became a rallying cry, and the work of Klint’s students—among them Børge Mogensen with his robust Spanish Chair (1958)—exemplified how factory-made simplicity could feel human-scaled and honest.

Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium (1933), with its cantilevered balconies and custom furniture, and Villa Mairea (1939), which wove local birch into organic spatial sequences, became pilgrimages for those seeking a humane Modernism.

Arne Jacobsen (1902–71) pushed the envelope further: his SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen (1958) was the first example of total design, from its soaring lobby to chairs like the Ant and Series 7, moulded in plywood and steel, anticipating the seamless integration of architecture and interiors.

These mid-century masters left a legacy that contemporary Scandinavian practitioners still reinterpret in light of new challenges. In Copenhagen, Norm Architects and Space Copenhagen draw on Klint’s proportional systems and Mogensen’s sturdy oak to craft furniture and lighting that honor traditional joinery but also respond to sustainability criteria and lean production.

In Helsinki, architects such as Arkkitehtitoimisto Mikko Summanen employ cross-laminated timber—an evolution of Aalto’s bent-wood experiments—to create office pavilions and housing that sequester carbon while maintaining the material’s inherent warmth and acoustic softness.

In Norway, Snøhetta’s multifaceted practice channels Aalto’s site-responsive ethos when designing public projects like the Lofoten Opera House (2013), whose gently sloping roof echoes windswept mountains and invites visitors to walk atop it. Internally, the firm’s furnishings blend Jacobsen’s finesse with vernacular wool textiles and leather, forging a dialogue between global Minimalism and local craft.

On Sweden’s west coast, architects like Wingårdhs reinterpret Scandinavian simplicity through dramatic concrete forms softened by pale timber detailing and generous daylighting—an echo of the Paimio tradition reimagined for 21st-century contexts.

Across design domains, the values first articulated by Klint, Aalto, and Jacobsen—human-centered proportions, material honesty, social purpose—have become touchstones. Danish company HAY commissions emerging designers to produce limited-edition pieces that toy with Mogensen’s democratic spirit, while Finnish studios like Hakola fuse Aalto-inspired curves with textiles woven from recycled fibres.

Even as climate imperatives demand radical rethinking of building processes, the Scandinavian conviction that good design must be accessible, sustainable, and soulful remains constant.

From the stave churches of the nineteenth century through the sleek welfare-state estates and total-design hotels of the mid-century, Scandinavian architecture and design have evolved by continually balancing tradition with innovation. Today’s practitioners, whether working in Oslo’s fjord-side neighbourhoods or Stockholm’s repurposed industrial districts, carry forward an inheritance of thoughtful craft, environmental attunement, and social responsibility—ensuring that the quiet, light-filled elegance born in the Nordic woodlands endures and adapts in an ever-changing world.