The Bauhaus School – Shaping Modern Design and Architecture

Where machines, art and architecture came together

In the last chapter of our pamphlet on the origins of Mid-Century Modern, we explored the Arts and Crafts movement, a response to the Industrial Revolution that aimed to preserve craftsmanship in design. We saw how figures like William Morris advocated for integrating art into daily life, creating a foundation for later movements to build upon.

Today, we move on to the Bauhaus school, which started in Germany in 1919. The Bauhaus took the Arts and Crafts movement ideas further, combining them with industrial processes while holding on to the belief that design could improve everyday life.

Before diving into the story of Bauhaus, I’d like to ask for 2 minutes of your time to fill out our first Substack survey. Your feedback will help us immensely in creating stories that match your interests. Thank you in advance for your contribution, and enjoy today’s story! Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments.

(Marco Guagliardo - Mid-Century Home’s Editor in Chief)

The Bauhaus school was born in a period of intense change. After World War I, Europe faced the challenges of reconstruction, rapid industrialization, and societal transformation. In this context, German architect Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus in Weimar, in 1919. His vision was revolutionary: a school that would unify arts, craft, and technology to create designs that were not only beautiful but also functional and accessible to all.

If you enjoy our stories, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription now to enjoy all our content and unlock the archive!

Gropius admired the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement, particularly its rejection of mass-produced goods and its focus on craftsmanship. However, he saw potential in the industrial processes that William Morris had resisted. For Gropius, machines were not the enemy; they were tools that, when guided by thoughtful design, could democratize access to well-made products.

The Bauhaus philosophy leaned on a few key ideas that shaped its approach. First, it sought to erase the boundaries between art and craft, a principle inherited from the Arts and Crafts movement but adapted to include industrial production. The Bauhaus rejected ornamentation and focused on design that served a purpose—echoing the modernist mantra that “form follows function.”

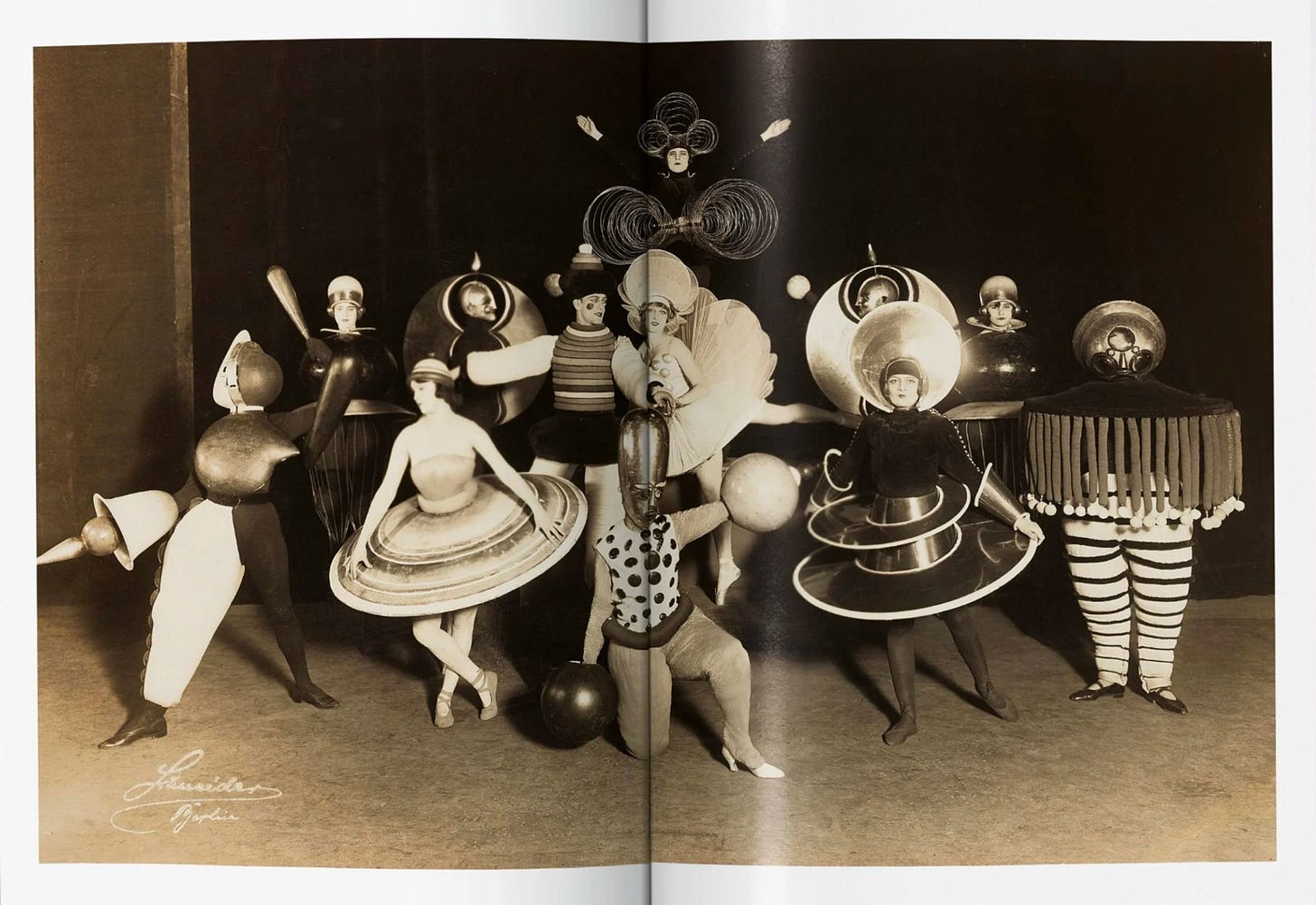

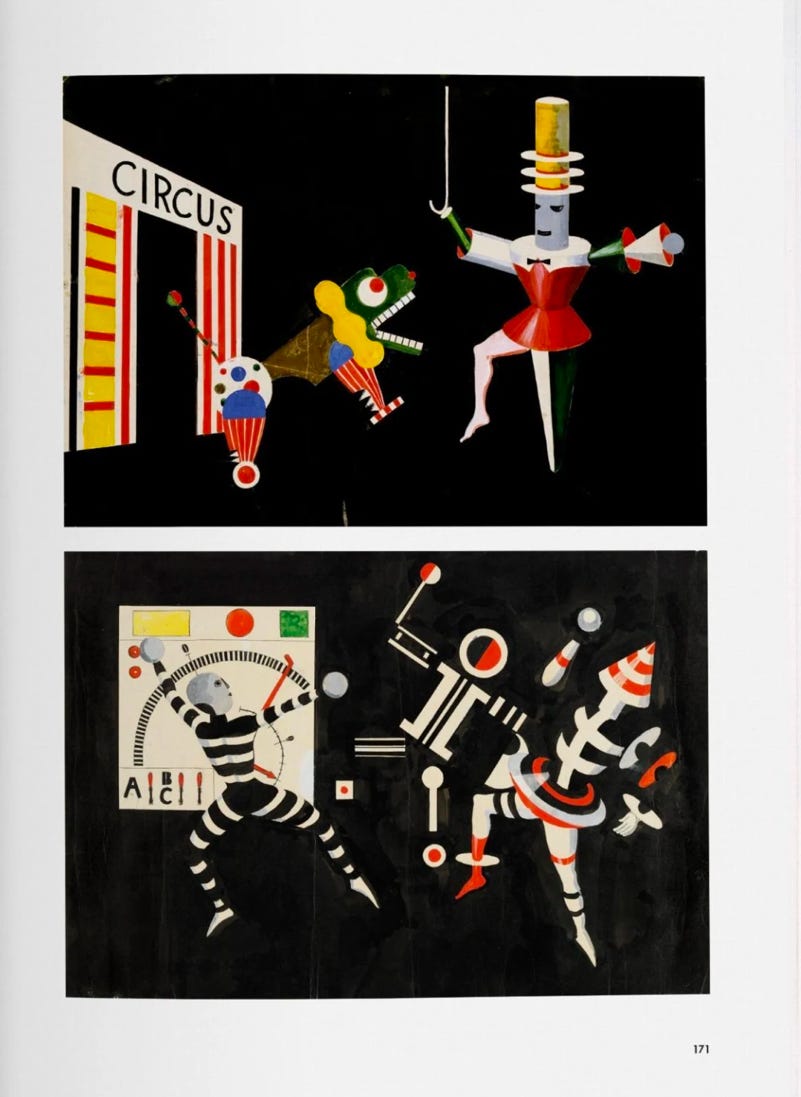

The school also fostered interdisciplinary collaboration. Architecture, furniture design, painting, textiles, and graphic arts were all part of the curriculum, encouraging students to see connections between different mediums. This holistic approach aimed to create a “total work of art,” where every element of a space was unified in design and purpose.

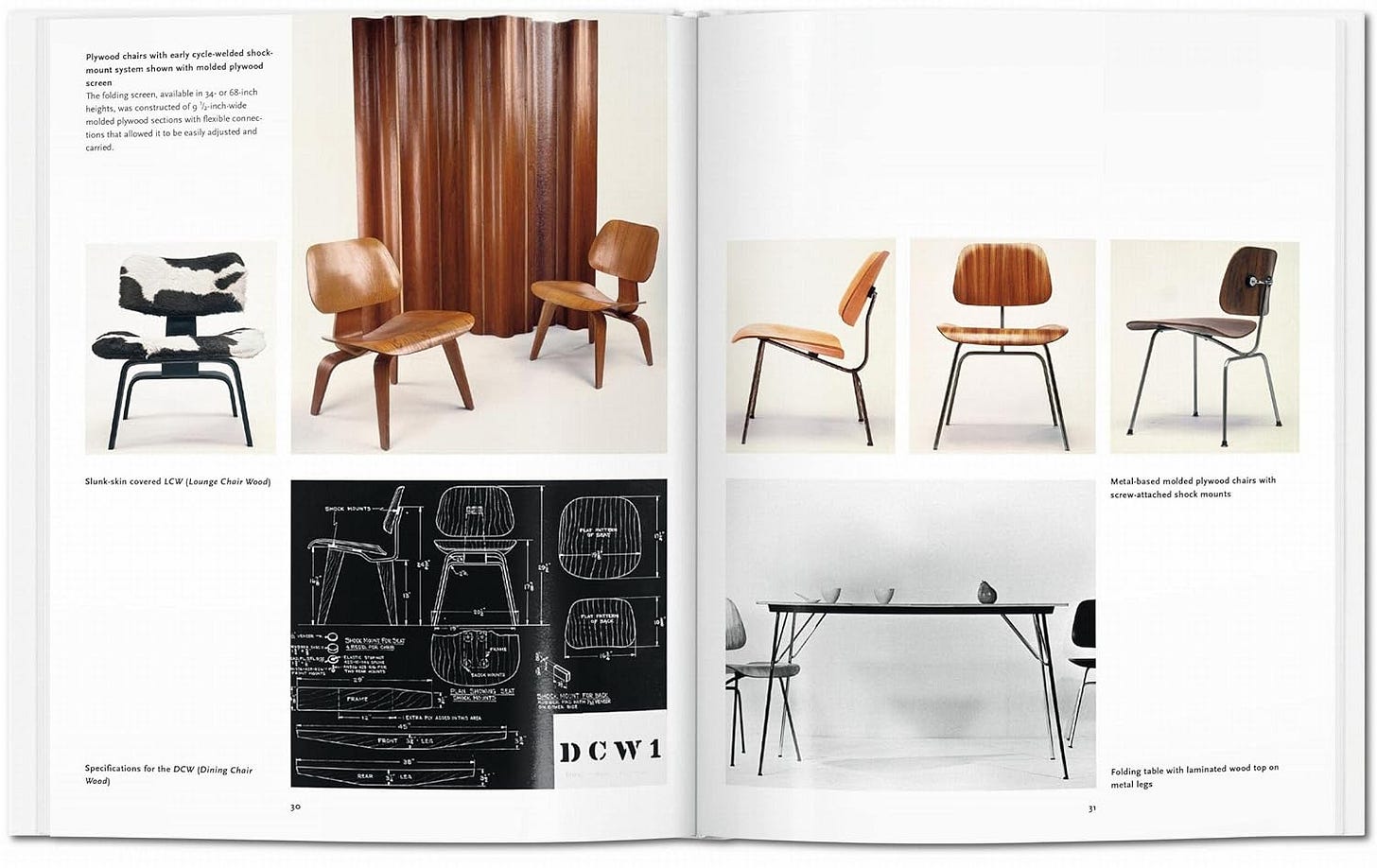

Experimentation was central to the Bauhaus ethos. Students and faculty explored new materials like tubular steel, plywood, and concrete, pushing the boundaries of what design could achieve. This innovation was evident in the work of figures like Marcel Breuer, who redefined furniture design with his Wassily Chair, and Marianne Brandt, whose geometric teapots demonstrated how functional objects could also be beautiful.

Enjoying this content? Upgrade to a paid subscription now to enjoy more stories!

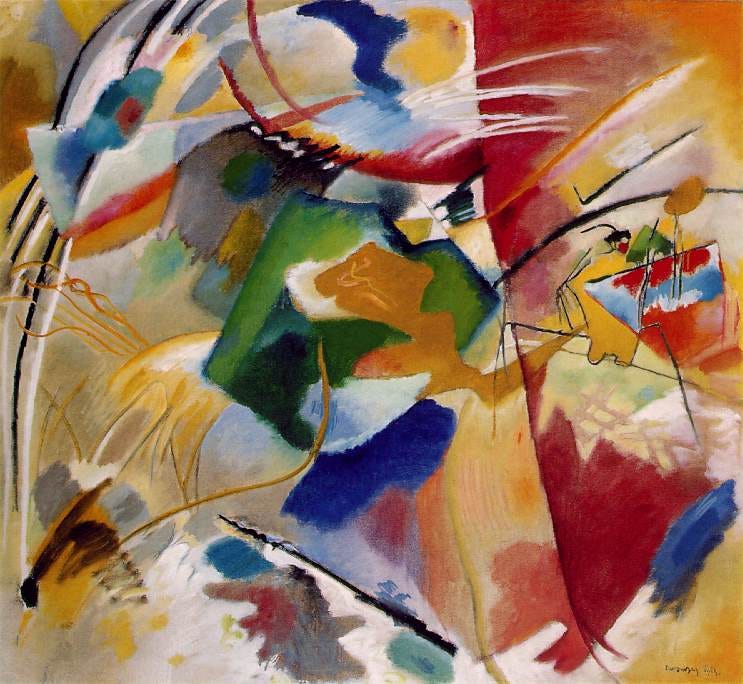

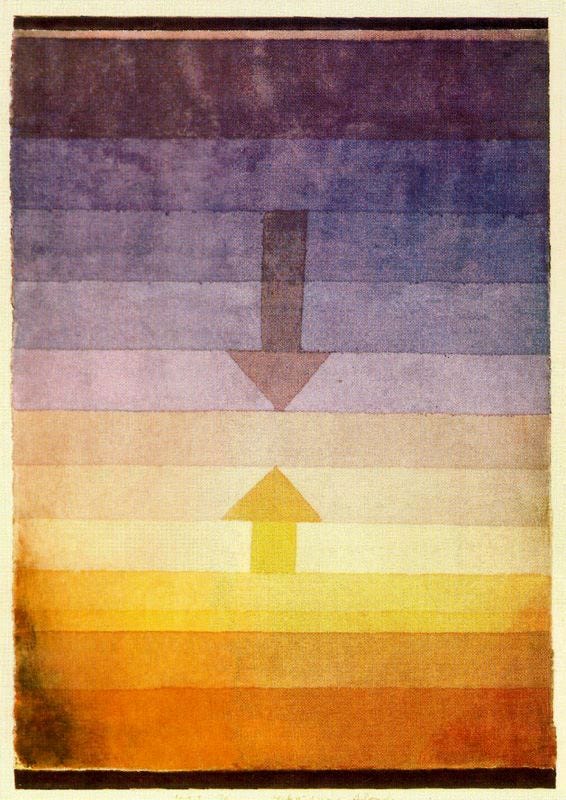

The Bauhaus attracted some of the most influential artists and designers of the 20th century. Gropius’s leadership was complemented by figures like Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee, who brought abstract and geometric principles to the school. László Moholy-Nagy emphasized the role of technology in art, while Mies van der Rohe, the school’s final director, introduced minimalist principles that would later define the International Style.

While the Arts and Crafts movement resisted industrialization, the Bauhaus embraced it, aiming to create products that were both well-designed and affordable. Furniture, textiles, and household items from the Bauhaus were stripped of unnecessary decoration, focusing instead on functionality and materiality. This approach resonated far beyond Germany, especially after the school was forced to close in 1933 under pressure from the Nazi regime.

Despite its closure, the Bauhaus’s ideas spread worldwide as its faculty and students emigrated. In the United States, Bauhaus principles found fertile ground. Designers like Charles and Ray Eames and Eero Saarinen adopted its emphasis on functional beauty, incorporating industrial materials and organic forms into their work. Josef Albers, a former Bauhaus faculty member, became a prominent figure in American art and design education, ensuring that the school’s methodologies influenced future generations.

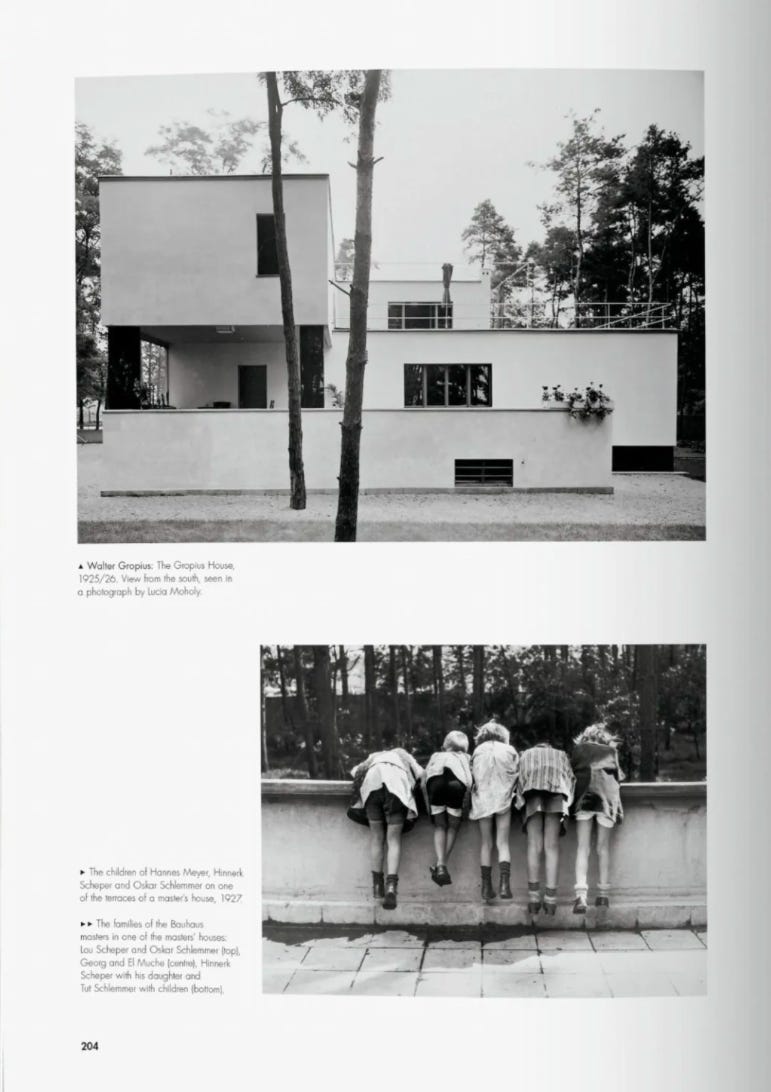

The Bauhaus also left an indelible mark on architecture. Its emphasis on clean lines, open spaces, and functional materials became hallmarks of modernist architecture, shaping buildings and interiors worldwide.

The connection between the Arts and Crafts movement and the Bauhaus lies in their shared belief that design could improve lives. While the Arts and Crafts movement focused on preserving traditional craftsmanship, the Bauhaus sought to harness the power of machines to achieve similar goals. Both movements rejected excessive ornamentation and championed functionality, creating a foundation for modernist design principles.

The Bauhaus remains one of the most influential schools of art and design in history. Its focus on functionality, simplicity, and collaboration still inspires designers today, influencing how we approach the objects and spaces around us.

In the next chapter, we’ll explore how the Bauhaus’s ideas evolved into the International Style, a global design language that carried modernism into the mid-century modern period. Stay tuned and don’t forget to let us know your thoughts in the comments.

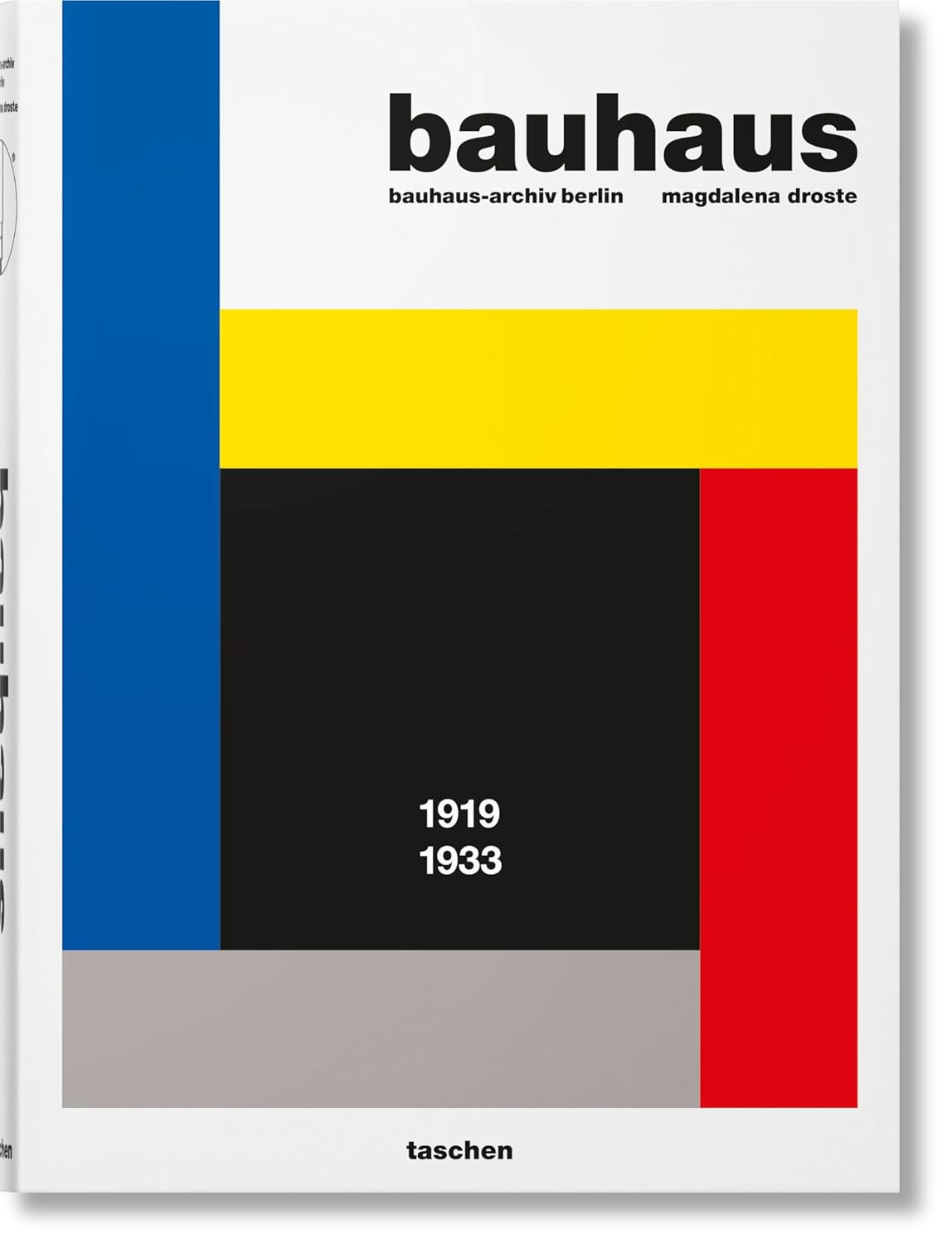

If you want to dig deeper into this topic, we recommend the book “Bauhaus” published by TASCHEN.

I totally agree that Magdalena Droste’s book Bauhaus is the perfect resource to learn more about this innovative school.