Scandinavian architecture and design transformed the 20th century—from rural farmhouses in Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and Norway to iconic structures in the United States and Australia. Today, we start a new article series to explore the historical forces and core values—human scale, natural light, and material honesty—that define the Nordic vision, spotlighting its most influential architects and designers.

Building on our earlier examination of Italian mid-century design and its transatlantic connections, we now reveal how Scandinavian innovation enriched the global modern movement.

By examining the story of mid-century modernism from different angles, we aim to uncover the enduring principles that continue to shape today’s design and architecture. We hope this series inspires you—please share your thoughts in the comments.

(Marco Guagliardo - Mid-Century Home’s Editor in Chief)

From the frost-bitten stave churches and simple farmhouses of rural Scandinavia in the late 19th century to the crisp, light-filled domestic interiors of 1950s Malmö and Oslo, Nordic design was born of both necessity and deep respect for craft.

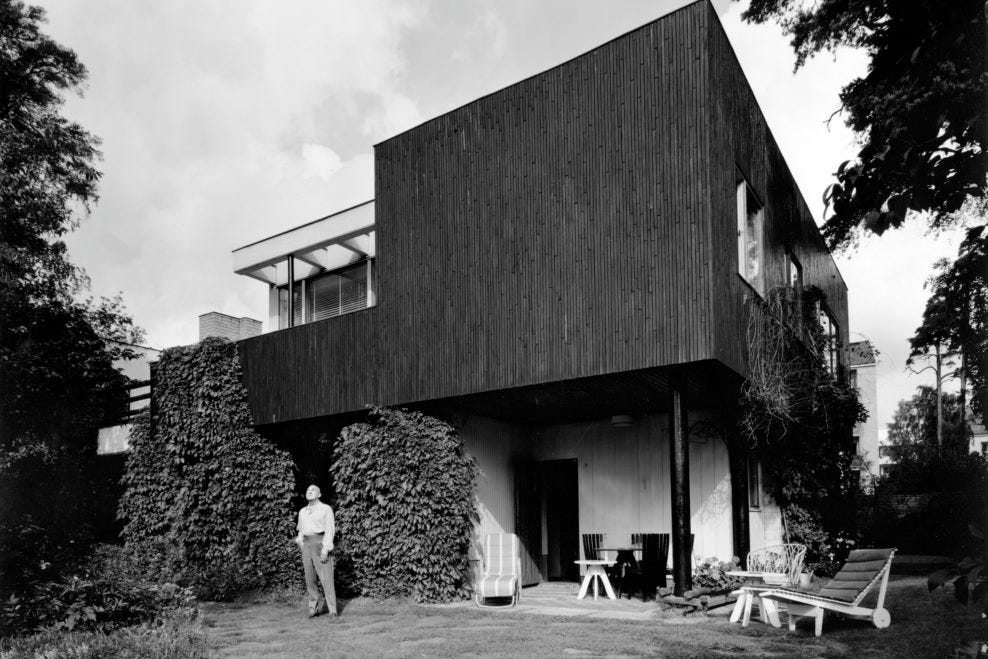

In the decades before World War II, designers such as Alvar Aalto in Finland and the Danish duo Kaare Klint and Poul Henningsen started simplifying traditional forms—traditional wooden joinery, hand-woven textiles, turf-roofed cottages—into pared-back furniture and lighting that celebrated honest materials and human scale.

Their work, rooted in the Arts and Crafts ethos and the emerging Functionalism of the 1920s, embraced bentwood techniques, laminated curves and a muted palette that offered warmth without ornament.

The disruption generated by WWII accelerated Scandinavia’s turn toward social democracy and collective rebuilding, and with it a new architecture of welfare: schools, housing estates and public buildings commissioned by burgeoning governments.

Faced with material shortages and a moral imperative to shelter displaced populations, architects leaned into modular construction, prefabrication and mass-produced furniture, codified in exhibitions promoted by organizations like Svensk Form (founded 1845, reconstituted 1943) and the UN’s post-war relief efforts.

Products such as Børge Mogensen’s “Spanish Chair” (1958) or Arne Jacobsen’s “Ant” chair (1952) exemplify the era’s mastery of factory-made simplicity, yet retain a tactile, humanist quality in their solid oak frames and hand-stitched leather.

By the late 1950s, as Scandinavia enjoyed growing prosperity, its aesthetic was exported through design magazines and the burgeoning trade fairs of Basel and Cologne.

American architects—particularly Richard Neutra and Craig Ellwood on the West Coast—and critics at Arts & Architecture magazine embraced the lightness of Nordic timber construction, integrating it into the Case Study Houses or suburban tract developments by Joseph Eichler. The open-plan living room with floor-to-ceiling windows, originally pioneered by Finnish modernists, became a West Coast staple, alongside plywood lounge chairs echoing Aalto’s experimental prototypes.

In sun-drenched Australia, architects like Robin Boyd, Neil Clerehan and Peter Muller translated Nordic ideals into a distinctly antipodean vocabulary—one that answered not only to light and landscape but to the ever-present risk of bushfire.

Boyd’s Walsh Street House (1952) pairs pale, breeze-catching screens with deep eaves that recall Scandinavian verandas. Clerehan’s Kapunda Road House (1964) deploys bleached timber walls and terracotta-toned textiles within an open plan, while louvered screens and sliding glass doors sustain natural cross-ventilation. Muller’s famed Gum House (1955) combines exposed jarrah beams and seamless indoor-outdoor flow—echoing Aalto’s organic forms but rooted in the eucalyptus-dappled site.

Throughout the ’60s and ’70s, small studios worked alongside the Australian Design Council to support furniture makers who, like Grant and Mary Featherston, favoured durable, easily repaired designs. These collaborations ensured that both buildings and interiors remained resilient, beautiful, and perfectly attuned to Australia’s unique climate.

Today’s dialogue between Nordic and global architecture and design practices remains rooted in those post-war ideals of affordability, sustainability and social good.

Contemporary Scandinavian architects revisit prefabricated timber pods and cross-laminated timber panels with digital precision, while also drawing on the human-scaled proportions and simple detailing first articulated by Aalto and Klint.

In turn, Australian and Californian firms reinterpret biophilic design—green roofs, integrated planting, passive solar strategies—through the lens of Nordic lightness, proving that the quiet elegance born in snow-dusted fjords still speaks fluently to climates and cultures from Melbourne’s scrubby hills to Los Angeles’s palm-lined streets.