Scandinavian Visionaries and the Birth of American Mid-Century Modernism

Bridging Fjords and Freeways

In the years following World War II, Scandinavian design offered Americans something they didn’t know they were missing: a quieter, more intentional way of living.

As the U.S. moved into a new era of prosperity and mass housing, Nordic architects and designers introduced an aesthetic that prioritised human scale, honest materials, and simplicity without coldness. Their work—refined through necessity and rooted in craft—found fertile ground in the American lifestyle.

This influence ran deeper than furniture. It reshaped the way homes were planned, built, and inhabited. Enjoy!

(Marco Guagliardo - Mid-Century Home’s Editor in Chief)

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, many European citizens, including many Scandinavian architects and designers, found themselves at a crossroads.

Although their countries had escaped the worst physical ravages of the conflict, the shared moral impetus to rebuild—and an acute awareness of Europe’s diminished markets—spurred many to look westward.

As early as 1939, the young Danish designer Jens Risom had arrived in New York, forging a partnership with Hans Knoll that would become Knoll Associates’ first furniture line.

After 1945, tours organized by New York’s Museum of Modern Art further amplified the reach of Scandinavian sensibilities: Hans J. Wegner, Finn Juhl, and others lectured on the virtues of democratic design, introducing their compatriots’ emphasis on honest materials and human scale to American architects, critics, and an aspirational middle class.

Once established in the United States, these émigrés both absorbed local conditions and reshaped them. Their Nordic preoccupation with daylight, born of long northern winters, found new expression in sweeping glass walls, open plans, and fluid indoor-outdoor connections more commonly associated with California modernism.

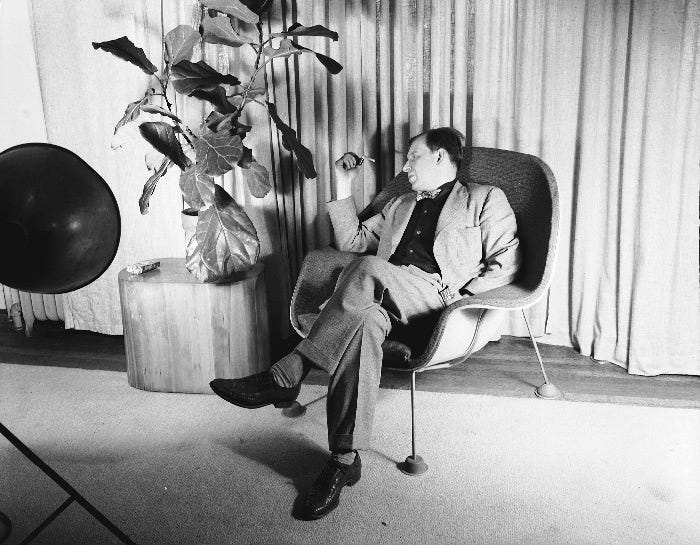

Eero Saarinen—himself the American-trained son of Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen—exemplified this synthesis at the Miller House in Columbus, Indiana (1957), where expansive glazing and integrated seating areas recall both his family’s legacy and the Case Study Houses on the West Coast.

At the same time, Scandinavian furniture designers forged critical industrial partnerships that embedded their aesthetic into everyday American life. Jens Risom’s early “knollwood” chairs—marked by woven straps and pared-back joinery—helped American consumers discover the warmth of wood.

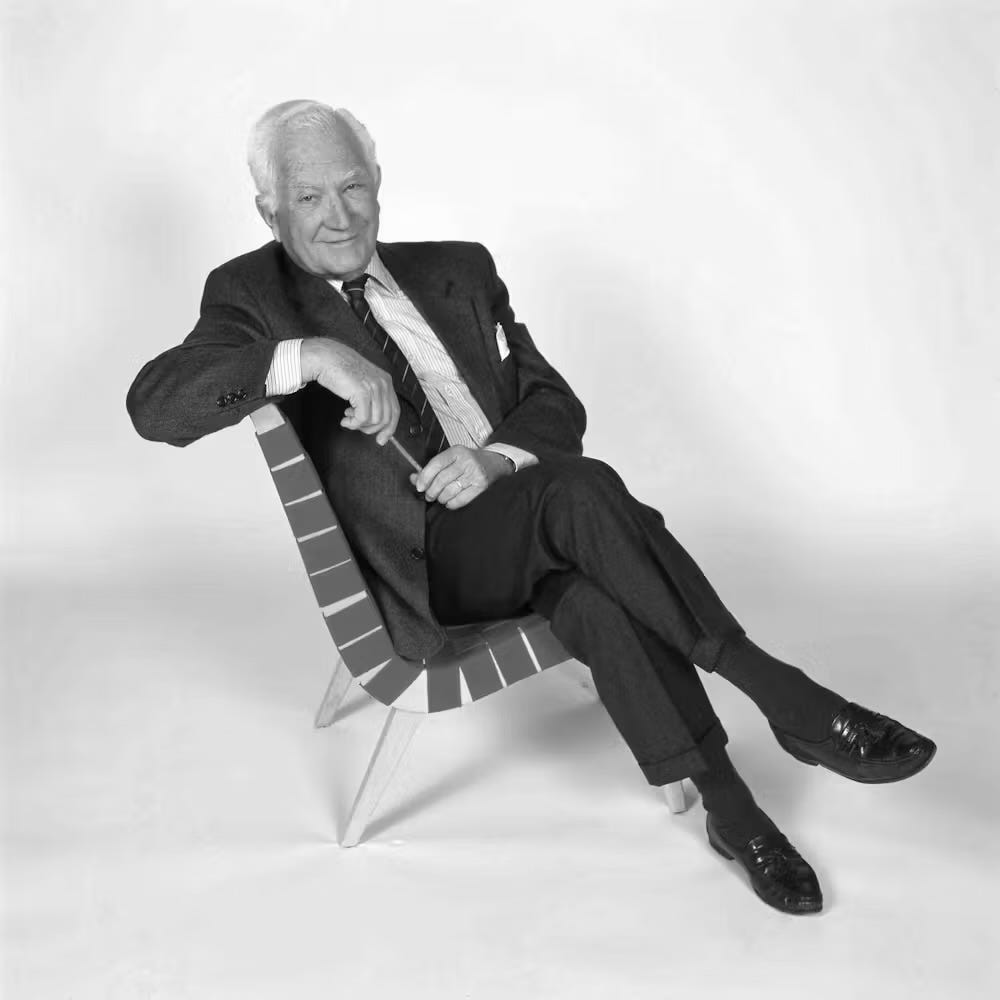

Finn Juhl’s sculptural lounge chairs, produced by Baker Furniture from 1955 onward, married organic forms with the scale and upholstery expectations of U.S. homes. And Alvar Aalto’s Paimio chairs and tea carts, curated by Florence Knoll in her Manhattan showroom, broadened Knoll’s catalog beyond its Bauhaus roots and signaled Americans’ appetite for Northern European craftsmanship.

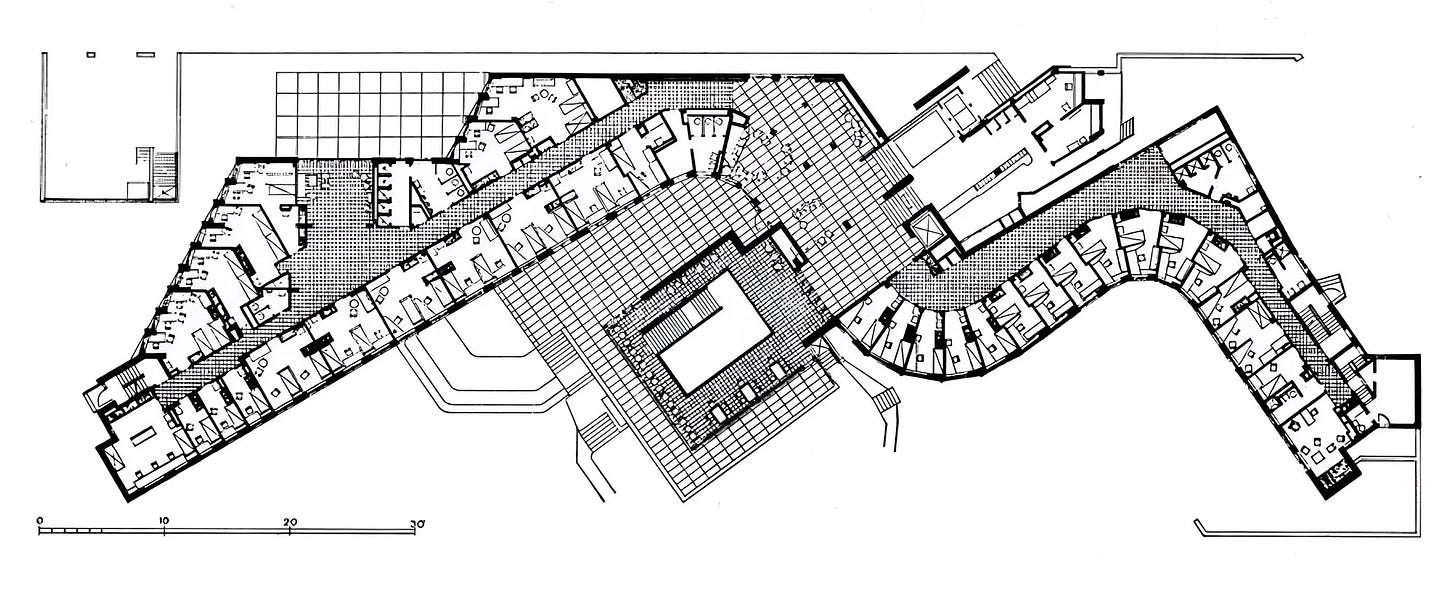

Architects, too, took note. Commissions for academic and civic buildings offered further platforms for Scandinavian innovation. Aalto’s Baker House dormitory at MIT (1949) demonstrated how mass housing could feel both economical and humane, its undulating façade and communal lounges echoing his Finnish precedents.

The SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen (1958), Arne Jacobsen’s integrated architecture-and-furniture project, became a case study in architecture schools from coast to coast, its Egg Chair and Swan Sofa entering corporate lobbies and university studios across America.

Between 1950 and 1955, MoMA’s annual Good Design exhibitions crystallized this transatlantic dialogue: nearly two-thirds of the objects on display were by Scandinavian makers.

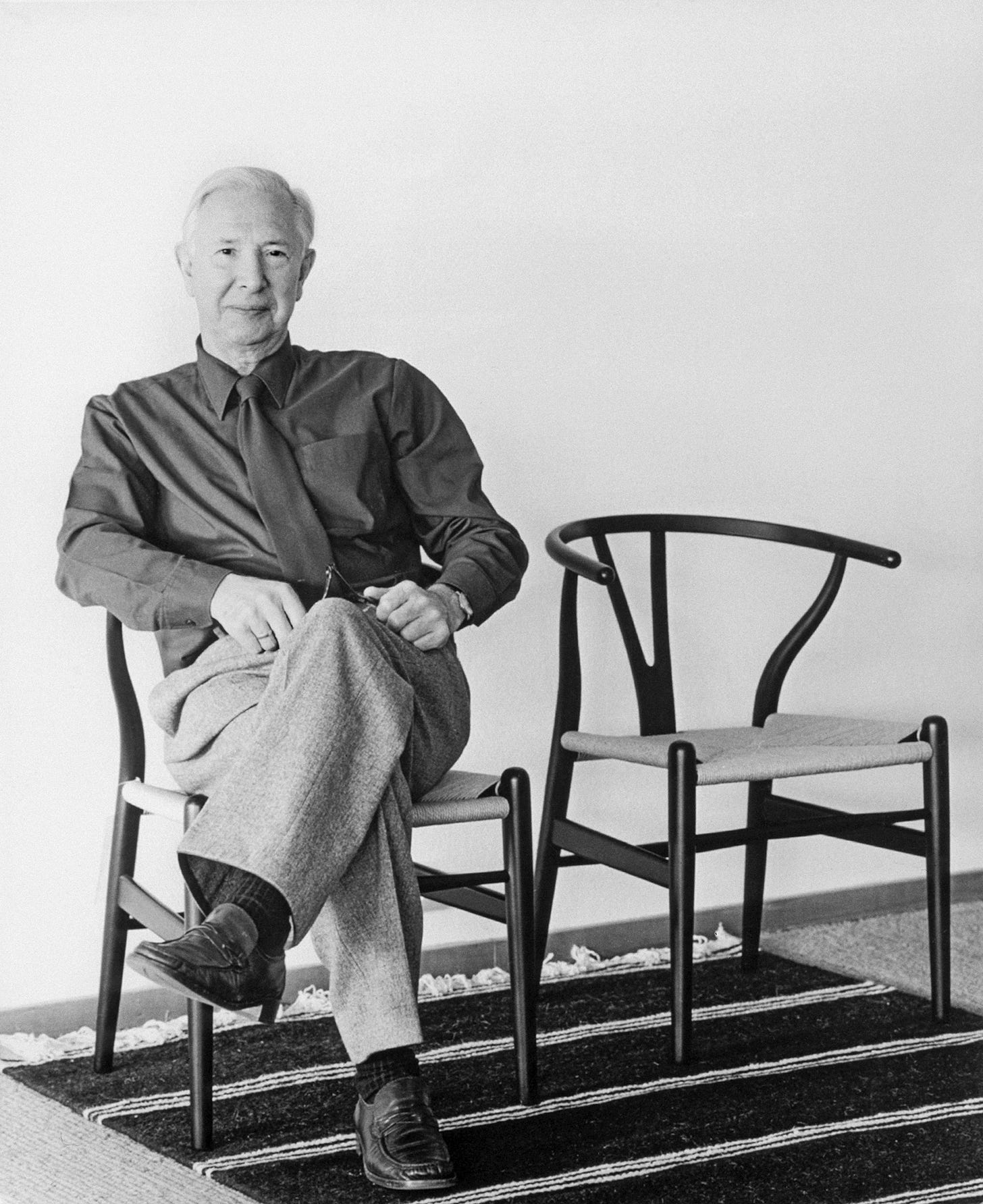

From Wegner’s Wishbone Chair to Kaare Klint’s Folding School Desk, these pieces encouraged U.S. manufacturers to prioritize wood’s tactile warmth and the virtue of slender, functional forms.

Department stores such as Macy’s in New York and Gump’s in San Francisco presented entire room settings built around these imports, making Nordic design both desirable and attainable for a broader public.

By the early 1960s, what began as a niche European import had permeated suburban tract houses, corporate campuses, and cultural institutions. Exposed timber beams once relegated to rural farmhouses now strutted through university chapels; minimalist lounge chairs in oak and leather nestled beside terrazzo coffee tables in executive suites.

Above all, American mid-century modernism absorbed the Scandinavian conviction that design ought to serve social good: housing should be economical without feeling austere; furniture should be mass-produced without sacrificing comfort; buildings should celebrate both the site and its inhabitants.

This reciprocal exchange—Scandinavian ideas refracted through the scale and optimism of post-war America, then re-exported as part of a global modernist vocabulary—reshaped the built environment on both continents.

The result is the enduring mid-century aesthetic: light-filled, human-centred, and balanced between craftsmanship and industrial efficiency. From the Knoll showroom to the Case Study House, from the MIT dormitory to the suburban living room, the quiet elegance born in the snow-dusted fjords found a second home under the broad skies of America.