Gio Ponti and the Reinvention of Italian Architecture and Design in the Mid-20th Century

How the mid-century master reimagined Italian modernism through architecture and design

As someone deeply fascinated by the intersection of architecture, history, and everyday life, I find architect Gio Ponti’s legacy incredibly relevant. His work not only helped shape Italy’s mid-century design identity but also redefined what it meant to live well in the modern age.

Today, we explore Ponti’s profound impact on post-war Italian architecture and design, a moment in history when the country was rebuilding not just its cities, but its cultural values and domestic ideals.

At a time when Italy was grappling with rapid urbanisation and industrial growth, Ponti’s architecture offered a uniquely Italian path to modernity—one that embraced innovation without abandoning tradition.

Through his buildings, his furniture, and his editorial work with Domus, Ponti championed a joyful, integrated approach to design that continues to inspire. Enjoy!

(Marco Guagliardo - Editor in Chief at Mid-Century Home)

Gio Ponti (1891–1979) occupies a unique position in the history of modern Italian architecture and design. With a career that spanned over five decades, Ponti’s influence touched nearly every aspect of Italy’s cultural rebirth in the post-war period.

From industrial design to interiors, from residential housing to landmark skyscrapers, Ponti not only shaped the built environment but also articulated a new vision of Italian modernity rooted in beauty, lightness, and flexibility. His contribution, best encapsulated in the notion of the “Casa all’Italiana,” revolutionised the way Italians lived and understood domestic space.

Historical Context: Italy After Fascism and War

The end of World War II marked a turning point for Italy. The country faced widespread devastation, political instability, and a desperate housing crisis. At the same time, the reconstruction era opened up unprecedented opportunities for architectural and industrial innovation.

Italian architects were forced to respond to new social realities: urban migration, the rise of the nuclear family, economic modernisation, and the need for efficient mass housing.

In this landscape, Ponti emerged as a cultural figurehead whose ideas married the avant-garde with national identity.

Educated at the Politecnico di Milano and initially working in a neoclassical style during the interwar years, Ponti’s post-war work demonstrated a keen understanding of Italy’s need to embrace modernity while remaining faithful to its artisanal and artistic traditions. In this, he stood apart from many of his contemporaries, who looked to the International Style for guidance.

Instead, Ponti synthesized international influences with a specifically Italian sensibility that prioritized elegance, lightness, and expressive form.

Values and Characteristics of Ponti’s Work

Ponti’s design philosophy was holistic. He saw no boundary between architecture, furniture, decoration, and art. His editorial work with Domus magazine, which he founded in 1928 and directed for decades, gave him a powerful platform to promote this integrated vision.

Through Domus, Ponti advocated for a “total design” approach in which interiors and architecture were developed in concert, and industrial production coexisted with high craftsmanship.

Several core values defined his work:

Lightness: Ponti was obsessed with achieving structural and visual lightness. Whether through the thin facades of his buildings or the refined elegance of his furniture, he sought to eliminate the heavy and inert.

Flexibility: He championed adaptable spaces, modular furniture, and mobile partitions, anticipating many principles of today’s flexible living.

Synthesis of Art and Industry: Ponti believed that mass production need not compromise beauty. He worked with manufacturers like Richard Ginori, Cassina, and Fontana Arte to create objects that were both functional and poetic.

Mediterranean Identity: Unlike the cold rationalism of Northern European modernism, Ponti’s work was infused with colour, pattern, and a strong sense of place. He drew inspiration from classical Italy, from the light and landscape to the artisanal traditions of ceramics, textiles, and woodworking.

Joy and Optimism: Ponti’s work always retained a sense of joy, playfulness, and optimism. He wanted design to improve everyday life—not through austerity, but through delight.

The “Casa all’Italiana”: Domesticity Reimagined

Among Ponti’s most enduring contributions is his concept of the “Casa all’Italiana.” In post-war Italy, the domestic space was undergoing radical transformation.

Traditional extended families were giving way to smaller, nuclear households; urban apartment living was replacing rural life. Ponti’s response was not only architectural but ideological.

The “Casa all’Italiana” was, for Ponti, a model of living that responded to modern life while preserving essential qualities of Italian domestic tradition. It emphasised:

Open and Light-Filled Interiors: Ponti rejected the dark, compartmentalised homes of the past. Instead, he used large windows, slender structures, and open plans to connect interior spaces and let in light.

Connection to Nature: The Italian house, in his vision, always maintained a dialogue with the outdoors through terraces, balconies, and loggias. This reconnected architecture to the Mediterranean way of life.

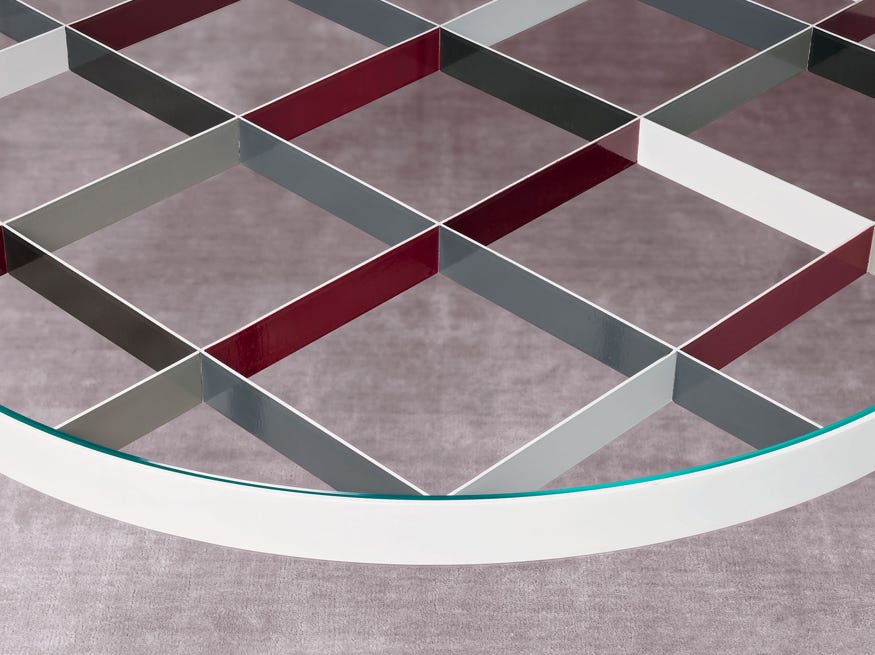

Integrated Design: From floor tiles to door handles, every detail was considered part of a coherent aesthetic. Ponti’s designs often featured built-in furniture, colour accents, and materials like glass, ceramic, and wood.

Economy and Elegance: The Italian house had to be accessible to the emerging middle class. Ponti’s designs were elegant but not extravagant, refined but not exclusive.

This domestic model was not a rigid style but a flexible ideal. It could be applied to apartments in Milan, villas in Caracas (such as the famous Villa Planchart), or even experimental furniture collections. It was deeply rooted in the belief that architecture should serve life—not the other way around.

Architectural Landmarks

Ponti’s architectural projects from the 1950s and 1960s vividly demonstrate his evolving approach to modern living. His own home and studio in Milan, the Via Dezza Apartment (1957), served as a true laboratory for the Casa all’Italiana, showcasing his integrated design ethos through built-in elements, custom furnishings, and a seamless blend of art and architecture.

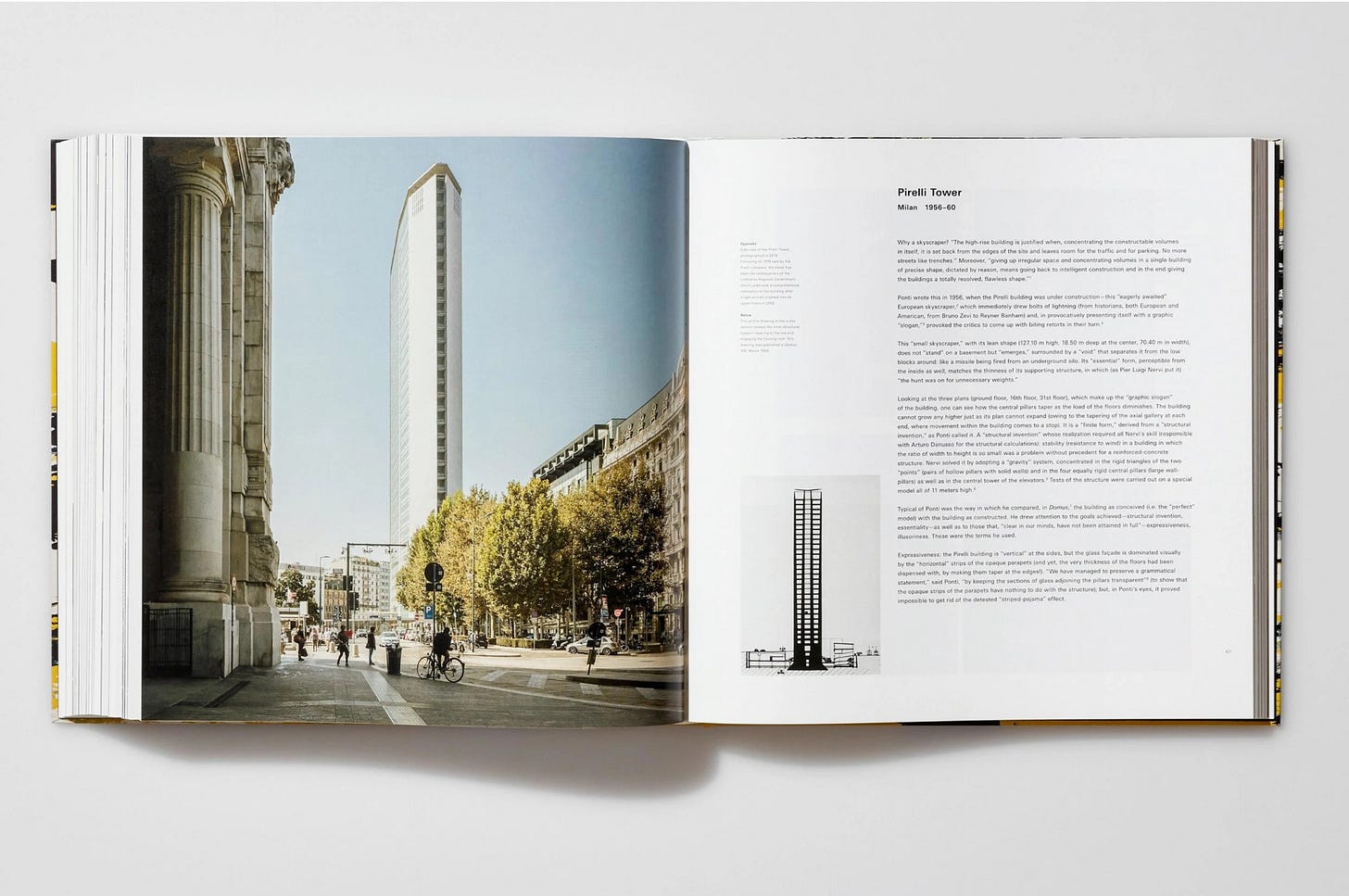

Around the same period, he designed the Villa Planchart in Caracas (1953–57) for a pair of Venezuelan clients—a striking example of mid-century architecture whose floating planes, openness, and decorative richness reflected Ponti’s ambition to export a distinctly Italian vision of style abroad. Meanwhile, the Pirelli Tower in Milan (1956–60), realised in collaboration with engineer Pier Luigi Nervi, became a national icon of post-war progress.

It embodied the city’s industrial resurgence and Italy’s renewed confidence on the world stage. Together, these projects encapsulate Ponti’s enduring commitment to innovation, beauty, and the human experience.

Legacy and Influence

Gio Ponti’s influence on Italian design is immeasurable. Through his teaching, writing, and prolific output, he shaped generations of architects and designers.

His ability to merge tradition with modernity, to champion both craft and industry, positioned him as a bridge between Italy’s past and future.

In today’s design discourse, Ponti’s ideas are enjoying a renewed relevance. As sustainability, adaptability, and user-centred design come to the forefront, Ponti’s emphasis on light, flexibility, and integration feels prescient.

The “Casa all’Italiana” remains a powerful model—not as a nostalgic ideal, but as a guide for how homes can be beautiful, functional, and intimately tied to their cultural context.

Ponti once wrote, “The house is a machine for living in—but not only that. It must be a joy.” His work reminds us that modern architecture need not be cold or anonymous; it can be joyful, colourful, and uniquely personal. For Italy and for the world, Ponti showed how design could be both forward-looking and deeply human.

In the post-war narrative of Italian architecture, Gio Ponti stands as a singular figure—an artist-engineer, a dreamer-pragmatist, and above all, a believer in the transformative power of beauty.

Resources

If you want to know and see more about Gio Ponti’s work, we strongly recommend checking the latest homage that publisher Taschen paid to the italian master: Gio Ponti is the most complete monograph on his work, spanning 60 years and 136 projects. Rich in photos, drawings, and rare materials, it captures his vision across all scales—from furniture to cities. Also available as an Art Edition with exclusive prints and a reproduction of the Arlecchino table.

I've attended Seminars and Concerts there. 🥰